New technology (first published by Tang et al. in 2009) allows genome-wide transcriptome data to be obtained from single cells, through the use of high-throughput sequencing (scRNAseq). Across a population of cells, the distribution of expression levels for each gene are obtained. An advantage of scRNAseq over other methods (e.g. bulk RNA-seq or single-cell real-time qPCR) is the increased cellular resolution and the genome wide scope. At present there is ample scRNAseq data that has yet to be thoroughly explored in the context of absolute quantification of mtDNA. It is intuitive to consider using the transcriptome of a single cell to infer its heteroplasmy, using for instance (sparse) linear regression (Murphy, 2012). Applying techniques for analysing scRNAseq data has the potential to achieve our goal of determining mtDNA heteroplasmy, and therefore understanding how scRNAseq data is processed is key.

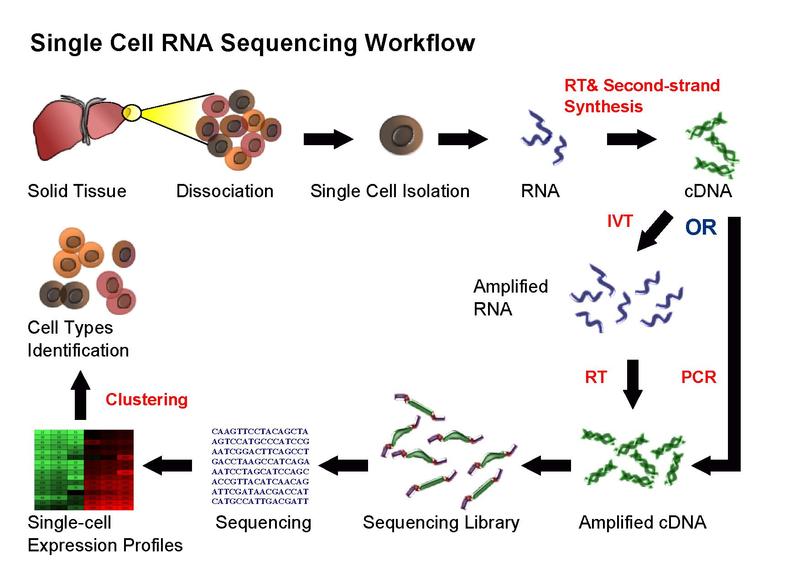

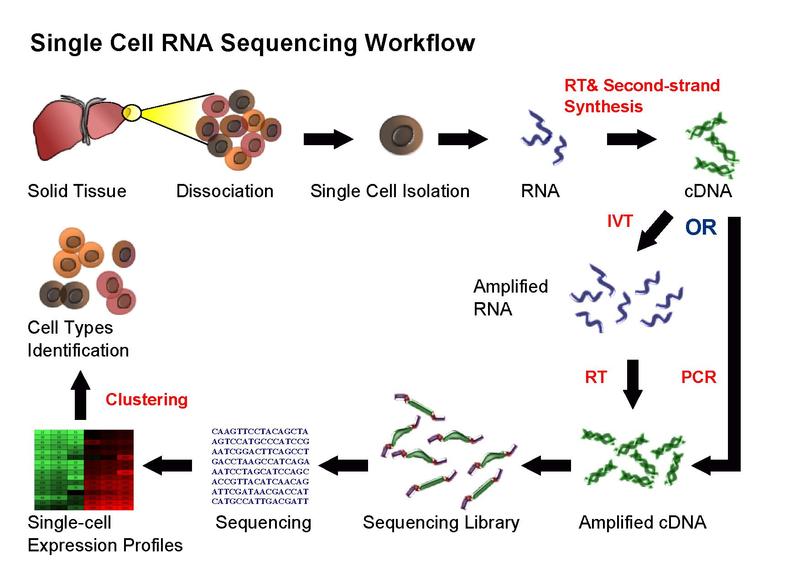

Figure 3: Single cell RNA sequencing workflow (source: Kiselev et al., 2018).

Figure 3 summarizes the overall scRNAseq workflow. RNA obtained from single cell isolation is fragmented, and cDNA is synthesized complementary to these fragments. The cDNA is amplified, forming a sequencing library. Reads are obtained after sequencing has occured. A 'read' refers to the sequence of a section of a unique fragment. A higher number of unique reads of each region of a sequence results in a higher 'sequencing depth'. Expression profiles are obtained through mapping, assigning reads to corresponding transcripts. If an RNA is expressed in high quantities, there will be more reads coming from it.

Kiselev et al., 2018 outline a scRNAseq pipeline that incorporates computational and statistical methods available. The ideal scRNAseq pipeline involves considering experimental design, processing reads, preparing the expression matrix, and interpreting biological analysis. Experimental design is important as it has implications on the biological analysis that can be carried out downstream. As each sequencing library represents a single cell, significant attention has to be paid to comparison of the results from different cells. Discrepencies are introduced due to low starting amounts of transcripts since the RNA comes from one cell only. It is possible to alleviate these issues through normalization and corrections.

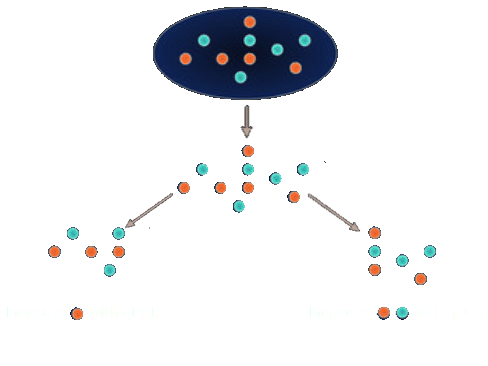

A main source of discrepancy between the libraries are gene ‘dropouts’, in which a gene is observed at a moderate expression level in one cell but is not detected in another cell (Kharchenko, Silberstein, and Scadden 2014). Dropouts potentially arise because a gene was not expressed in the cell and hence there are no transcripts to sequence. However, dropouts can also be a result of experimental shortcomings: a gene was expressed but transcripts are lost prior to sequencing, or sequencing depth is not sufficient to produce any reads.

One possible solution to this problem is to impute the dropouts in the expression matrix, 'filling in' the missing values and data. Two available imputation methods are MAGIC (van Dijk et al. 2017) and scImpute (Li et al. 2018). MAGIC imputes missing expression values by sharing information across similar cells, based on the idea of heat diffusion. scImpute determines which values are affected by dropout events based on a mixture model which learns each gene’s dropout probability in each cell.

The scRNAseq techniques described by Kiselev et al. can in principal be applied to mitochondria and mtDNA in order to quantify heteroplasmy. Additionally, in order to study the effects that mtDNA heteroplasmy has on nuclear DNA, transcriptomes of cells with varying heteroplasmy can be compared.

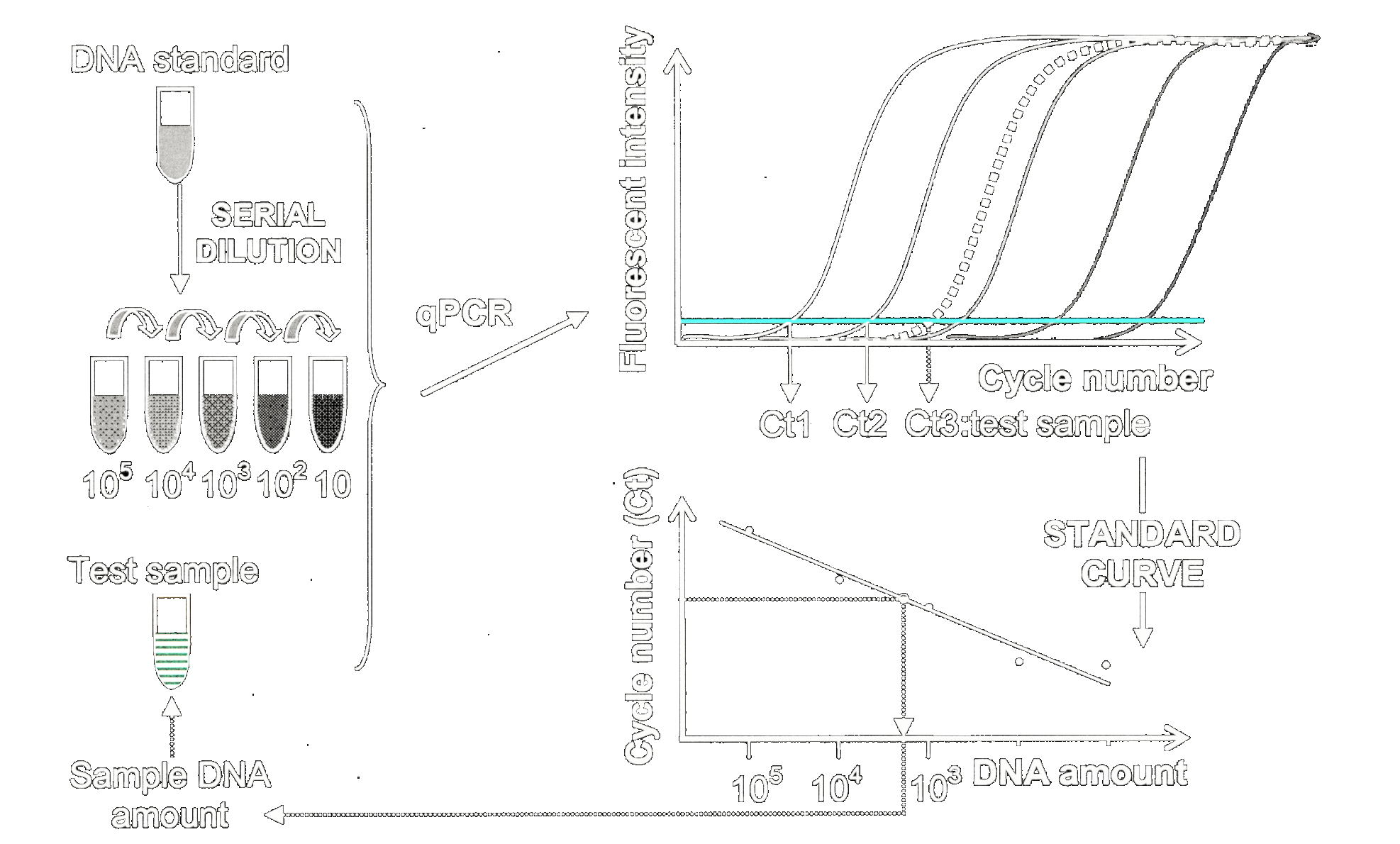

An alternative approach uses qPCR data for quantification of heteroplasmy in mtDNA, which is the main focus of this project henceforth.